If you’ve worked with Python for any length of time, you know how easy it is to just… pass things around.

You write a function, and you throw in a few parameters:

configure_device(3, "admin", True)And yeah — it runs. No errors. No fuss.

But let’s stop and look at that:

- What does

3represent? A port number? A device ID? Something else? - Is

"admin"a username, a role, or a mode the device should operate in? - And

True— does it mean “enabled”? “debug mode”? Is it confirming a condition?

From Python’s perspective, this is perfectly legal. It doesn’t care what those values mean. As long as the types line up, it’s happy. But for myself — including me — this is a mess waiting to happen.

Raw Values Hide Meaning

We call these raw values: primitive types (like integers, strings, booleans) that don’t say anything about what they are.

They’re easy to write, but hard to read.

They’re fast to code, but slow to understand.

They pass tests — until they don’t.

Imagine reading this six months from now:

connect_to_service(1, 2, "secure", False)Can you guess what any of those parameters mean without looking up the function?

Would you feel confident changing one of them?

Would you want your new intern to debug this?

Why This Happens in Python

Some languages — like Java, Rust, or Kotlin — tend to push you toward defining small classes, enums, or constants to give values meaning. The compiler will often complain if you misuse them, and the IDE can guide you with suggestions and hints.

Python? Not so much.

In Python, you can pass a 0, a "start", or None, and nobody stops you. It’s part of what makes Python fun and flexible — but it also makes it easy to write ambiguous, fragile, or undocumented code.

If your project grows past a few hundred lines — or a few developers — this flexibility becomes technical debt. You end up writing comments to explain what parameters mean, or worse: guessing, debugging, and backtracking to figure it out.

The Better Way: Value Objects

So what’s the alternative?

Instead of passing raw values, I use Value Objects — small classes that wrap a single value, but with structure, validation, and most importantly: meaning.

Rather than this:

spi.open(0, 1)I write this:

spi.open(SPIBusNumber(0), SPIChipSelect(1)Now, I know exactly what those numbers represent — and if I pass something invalid, the object will complain immediately.

Value objects are like guardrails for your functions:

They help your code explain itself.

They protect you from yourself.

They make your Python more human — and more professional.

In the rest of this post, I’ll show you how I design them, why they work, and how they’ve saved me (and my intern) from a lot of head-scratching.

Let’s get into it.

The Goal: Self-Documenting, Validated Values

I wanted a better way — something that:

- Captures intent

- Validates inputs early

- Prevents misuse

- Works naturally with Python type hints

- Looks clean in code reviews

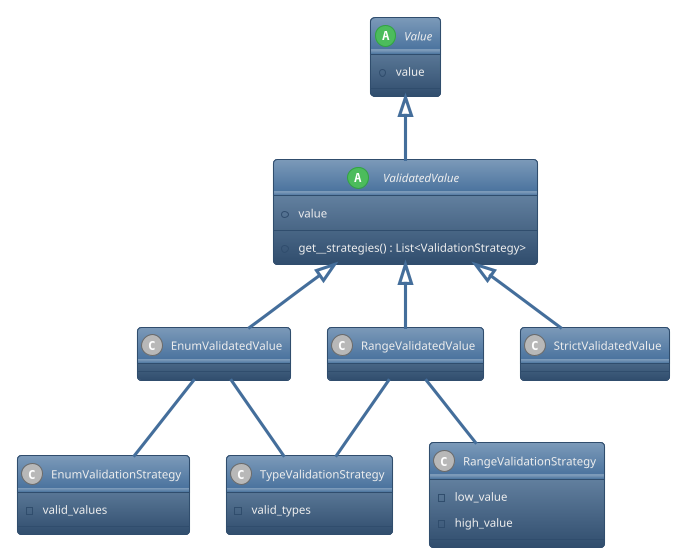

Enter: the Validated Value Object pattern.

Building Blocks: The Value Class

Here’s the base Value class. It provides comparison methods, encapsulates the value, and sets the foundation for specialization:

class Value(Generic[T]):

"""

A base class to represent a generic value. Provides comparison methods for equality, less than,

and less than or equal to comparisons between instances of derived classes.

"""

def __init__(self, value: T):

self._value = value

@property

def value(self) -> T:

"""Returns the stored value."""

return self._value

def _compare(self, other, comparison_func):

if isinstance(other, self.__class__):

return comparison_func(self.value, other.value)

return False

def __eq__(self, other):

return self._compare(other, lambda x, y: x == y)

def __lt__(self, other):

return self._compare(other, lambda x, y: x < y)

def __le__(self, other):

return self._compare(other, lambda x, y: x <= y)

It’s clean and minimal. But it doesn’t validate anything—yet.

What Is This Class Trying to Do?

This Value class is the foundation for building what are often called value objects — objects that:

- Wrap a single, primitive value (like an

int,str,float, etc.) - Carry semantic meaning (e.g.,

PortNumber,Username,IPAddress) - Can be compared meaningfully

- Are treated as logically equal if their underlying value is equal

It’s not a replacement for primitive types — it’s a wrapper that adds meaning and safety. So instead of just passing around 42, you can pass PortNumber(42), which your IDE and collaborators can immediately understand.

Line by Line Breakdown

from typing import Generic, TypeVar

T = TypeVar('T')

class Value(Generic[T]):

def __init__(self, value: T):

self._value = value

@property

def value(self) -> T:

return self._value

T = TypeVar('T')

This defines a type variable named T.

Think of T as a stand-in for any type. It could be int, str, float, bool, a custom class — whatever you want this class to wrap.

This is used to make your class generic — able to work with any one type, while still keeping that type consistent across its methods and properties.

class Value(Generic[T])

This declares the Value class as generic over the type T.

It’s basically saying:

“This class uses a type variable

T, and wherever I referenceTinside, I expect you to tell me what that is when you subclass or instantiate it.”

def __init__(self, value: T):

This tells Python (and your IDE/type checker) that:

- The constructor should only accept a value of type

T. - That same type

Twill be used consistently within the instance.

So, for example, if T is int, this constructor only accepts an int. If it’s str, only a str, and so on.

@property def value(self) -> T

This accessor method ensures that:

- The type returned is the same type

Tthat was passed in.

It’s consistent and type-safe — even if T is something like a CustomID class, or a datetime.

Real Usage: What Does It Look Like in Practice?

Let’s say you subclass this class to make something meaningful:

class PortNumber(Value[int]):

pass

class Username(Value[str]):

pass

Now you get:

port = PortNumber(8080)

username = Username("mike")

# Accessing the values

print(port.value) # 8080

print(username.value) # "mike"

# Type checkers know:

# port.value is an int

# username.value is a str

Your IDE now knows:

- What the type is (

intorstr) - What autocomplete options to suggest

- Where to warn you if you do something like

port = PortNumber("oops")

So even though Value is a single class, it adapts to each use case — safely and intelligently.

So what are the other methods used for,

__eq__: Equality Comparison

Purpose:

Allows comparison between two Value objects of the same type using ==.

Example:

port1 = PortNumber(8080)

port2 = PortNumber(8080)

port3 = PortNumber(443)

print(port1 == port2) # True, because values are equal and type matches

print(port1 == port3) # False

print(port1 == 8080) # False, different type (not a PortNumber)

What’s Happening Internally:

port1 == port2calls__eq____eq__uses_compare, which:- Confirms both are instances of

PortNumber - Applies the lambda:

lambda x, y: x == y

- Confirms both are instances of

__lt__: Less Than Comparison (<)

Purpose:

Allows sorting and comparison using <

Example:

port1 = PortNumber(443)

port2 = PortNumber(8080)

print(port1 < port2) # True

print(port2 < port1) # False

Real-world use:

Useful in sorting:

ports = [PortNumber(8080), PortNumber(80), PortNumber(443)]

sorted_ports = sorted(ports)

print([p.value for p in sorted_ports])

# Output: [80, 443, 8080]

__le__: Less Than or Equal (<=)

Purpose:

Allows you to compare values inclusively

Example:

port1 = PortNumber(443)

port2 = PortNumber(443)

port3 = PortNumber(8080)

print(port1 <= port2) # True (equal)

print(port1 <= port3) # True (less)

print(port3 <= port1) # False

_compare: DRY Comparison Helper

This is an internal utility method that all the other comparison operators use. It keeps your comparison logic:

- DRY: Write it once, reuse for

==,<,<= - Safe: Only compares if both objects are of the same type

- Flexible: Accepts any comparison function (

==,<, etc.)

You wouldn’t call _compare directly, but it simplifies your code behind the scenes.

Quick Demo Recap:

p1 = PortNumber(22)

p2 = PortNumber(80)

p3 = PortNumber(80)

print(p1 < p2) # True

print(p2 == p3) # True

print(p2 <= p3) # True

print(p1 == 22) # False – different type

Closing Thoughts

Python is a joyfully expressive language, but with that freedom comes a responsibility: to write code that’s not just functional, but also clear, intentional, and maintainable.

Using Value Objects has helped me bridge the gap between Python’s flexibility and the kind of structured, self-explanatory code I want to write and read — whether it’s for myself, my team, or my intern who’s just getting started.

It’s a simple shift: wrap your raw values in something meaningful. But the payoff is huge — fewer bugs, better communication, stronger tooling, and code that tells its own story.

So the next time you’re about to pass 42, "admin", or True into a function… stop.

Ask yourself: what does this really mean?

Then give it a name — and let your code reflect your intent.

code for reference: https://github.com/OODesigns/universal-control-hub