It was a rainy Tuesday afternoon, around 2pm, when I connected with my intern.

“How are you doing?” I asked.

She didn’t look thrilled.

“I’ve been assigned to a new project,” she began. “I can choose between Python and Java. I started with Python since there was already a placeholder project—with libraries and some skeleton code. But… I just don’t understand any of it.”

“There’s so much existing code. But unless I stop and look everything up, I have no idea what the method arguments are supposed to be, or what I can actually do with them.”

Then she paused, almost embarrassed.

“I think I’m going to start again—with the Java version. At least I can tell what each argument is supposed to do.”

And honestly?

I get it.

When Python Gets in the Way

I’ve seen this same story play out more than once.

Many Python projects aren’t crafted—they’re simply coded. Developers move fast. They skip documentation. They assume that because Python doesn’t enforce types, structure and clarity aren’t needed.

But here’s the thing: Python’s flexibility is both its superpower and its Achilles’ heel. Without types, it’s easy to lose sight of a developer’s intent. You don’t know what methods are available, what parameters are expected, or what shape the data should take—unless you dig through the source or guess.

Personally, I make Python work for me.

I lean heavily on type annotations. Not because I have to—but because they make my intent clear, both to myself and others. They act as guardrails. They help my IDE help me. They allow collaborators (and interns!) to understand what’s going on without reading between the lines.

And honestly? It helps me, too.

Reading Temperature Over SPI

Let’s ground this with a real-world example.

Imagine you’re trying to read the temperature from a sensor. The sensor doesn’t return a temperature like 22.5°C. Instead, it sends an analog voltage signal that represents the temperature. To read this data digitally, you’d typically use an ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter)—like the MCP3008—which communicates via SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface).

What Is SPI?

SPI is a communication protocol that lets a computer (or microcontroller) talk to peripherals like sensors, displays, and ADCs. It works over four wires:

MOSI(Master Out, Slave In)MISO(Master In, Slave Out)SCLK(Clock)CS(Chip Select)

In this setup, the Raspberry Pi would be the “master,” and the MCP3008 ADC would be the “slave.”

Using the spidev Library

In Python, the spidev library gives you direct access to the SPI bus on Linux systems. Here’s a simple example:

import spidev

spi = spidev.SpiDev()

spi.open(0, 0) # Bus 0, device (chip select) 0

to_send = [0x01, 0x02, 0x03]

response = spi.xfer(to_send)

This code technically works. But… what does [0x01, 0x02, 0x03] actually mean? What are the valid values? What does open(0, 0) do?

Looking at the method signature doesn’t help much either:

def open(self, bus, device):

"""

open(bus, device)

Connects the object to the specified SPI device.

open(X, Y) will open /dev/spidev<X>.<Y>

"""

passCode That Explains Itself

I didn’t want to look this stuff up every time. I wanted self-documenting code.

So I started with a simple builder pattern:

class SPIClientBuilder:

def set_bus(self, bus):

self._bus = bus

return self

def set_chip_select(self, chip_select):

self._chip_select = chip_select

return self

But this version accepts anything. There’s no validation, no guardrails, no clarity.

Adding Type Annotations

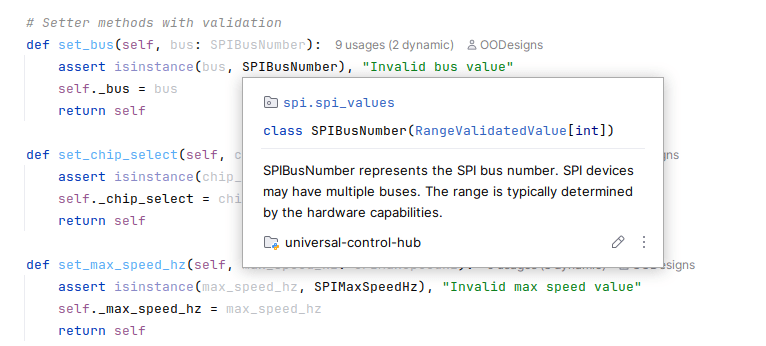

I rewrote it using type annotations and some small domain-specific classes to enforce structure and clarity:

class SPIClientBuilder:

def set_bus(self, bus: SPIBusNumber):

assert isinstance(bus, SPIBusNumber), "Invalid bus value"

self._bus = bus

return self

def set_chip_select(self, chip_select: SPIChipSelect):

assert isinstance(chip_select, SPIChipSelect), "Invalid chip select value"

self._chip_select = chip_select

return self

Now the code expects meaningful, structured types instead of raw integers. These types carry their own validation and semantics.

Small Classes With Big Impact

Here’s how I define something like SPIBusNumber:

class SPIBusNumber(RangeValidatedValue[int]):

"""

SPIBusNumber represents the SPI bus number.

SPI devices may have multiple buses. The range is typically determined by the hardware.

"""

def __init__(self, value: int):

# SPI bus numbers are typically 0–7

super().__init__(value, int, 0, 7)

Now, when I come back six months later, I don’t have to remember what the valid range is. It’s right there in the class. It also shows up in the IDE, in autocomplete, and in docs.

What’s RangeValidatedValue?

For the curious: RangeValidatedValue is a base class I use for all value types. It ensures that the value:

- Is of the correct type.

- Falls within a valid range.

Why bother? Because I believe an object should be valid from the moment it’s created. It makes the rest of my code cleaner, safer, and easier to reason about.

Final Thoughts

Python gives you a lot of freedom—but without structure, that freedom can become chaos. You don’t have to use type annotations or validation classes. But when you do, your code becomes more expressive, more robust, and easier to work with—for everyone, including future you.

So yes, my intern chose Java. And honestly, I don’t blame her.

But that moment was also a great reminder: just because Python doesn’t force us to write readable, structured code doesn’t mean we shouldn’t.

Code can be found here: